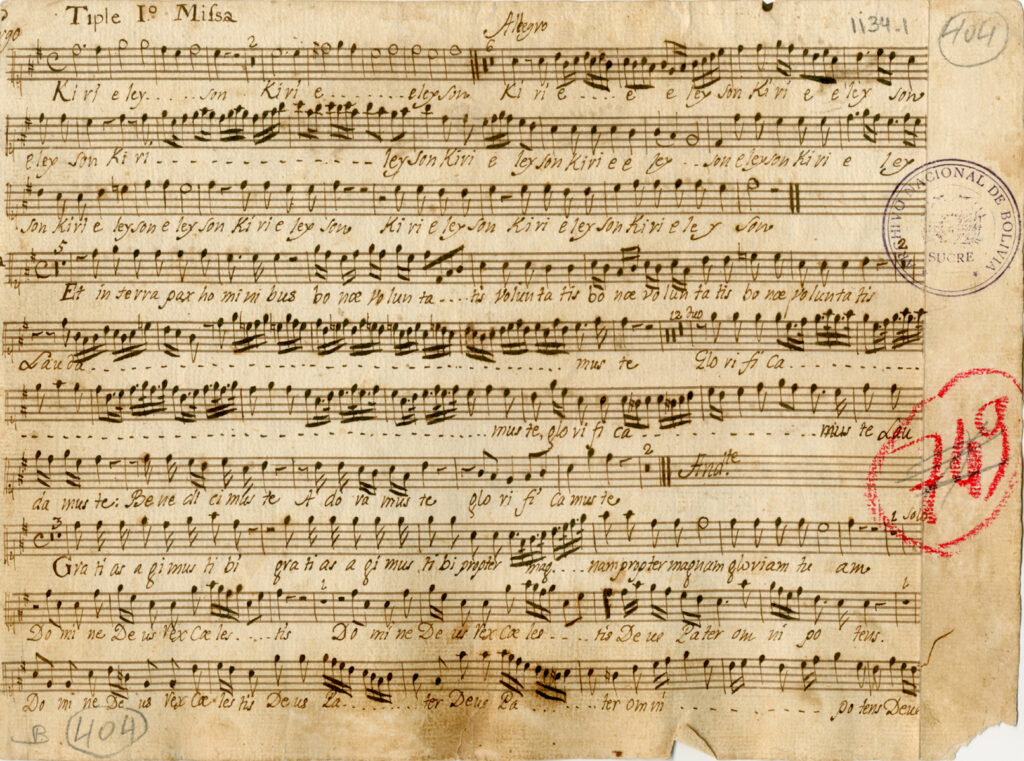

My fourth and current book project, Colonial Galant, concerns music made in the Jesuit missions of eighteenth-century Chiquitania (Bolivia). Archival sources related to Jesuit missions in this part of the world preserve several operas and large-scale liturgical compositions written entirely in the Chiquitano language and attributed to Indigenous composers. Unlike the heavy counterpoint of other New World sacred music, this repertoire is characterized by transparent textures, simple harmonies, and regular rhythms. It is a pendant to the European galant style. My book will be the first English language monograph on this remarkable

development in music history. In it, I reinterpret the musicological narrative of the galant style, situating it for the first time in a global frame. My essay on this topic, “Colonial Galant: Three Analytical Lessons from the Chiquitano Missions,” appeared in our discipline’s flagship publication, The Journal of the American Musicological Society. In November of 2024, this article won the Society for Music Theory’s prestigious Outstanding Publication Award, which is given annually for an exemplary publication authored by a senior scholar.